A family’s escape

from Kuwait

One Indian family talks of how they left Kuwait, 23 days after Iraqi invasion

Dubai: It’s been 30 years since that fateful day, but the horrors of the Gulf War continue to haunt the Ashar family, who found themselves homeless and separated from loved ones as events unfolded in a matter of hours.

Some may call it a cruel twist of fate, others could lay blame over the actions of a despot, but for the residents of Kuwait, life forever changed on the day Saddam Hussein decided to march on to the Gulf state and declare Iraqi sovereignty. Thirty years can be a lifetime for many, but for eldest daughter Kiron Khira, who was 7.5 months pregnant at the time of the Iraqi invasion, the scars continue to run deep.

The former Kuwaiti resident was in Dubai at the time with her mother Shanta, 24 hours away from returning home to deliver her older daughter. “We were scheduled to return home on August 3 to join my father who was in Kuwait at the time, when all hell broke loose,” recalls Kiron.

At 2am on August 2, Iraqi forces entered Kuwait and overwhelmed the home nation’s defence forces. Within hours, Kuwait City was captured and the Iraqis established a puppet regime, declaring martial law. Kiron’s father, Ramesh Ashar, whose home was blocks away from the Kuwaiti Emir’s palace, says it wasn’t until the first light of dawn that he realised something was amiss.

“It was 6.30am when the commotion outside alerted me that something wasn’t quite right,” he tells Gulf News. “I immediately called up my wife in Dubai and explained what was happening outside our home, while still unable to decipher the truth of the situation.” The vista before him seemed unreal as Iraqi tanks and armed guards were patrolling the street below, while fighter jets flew overhead — all headed in the direction of the Emir’s palace. A few hasty calls later, the family was able to piece together what had transpired as they lay sleeping.

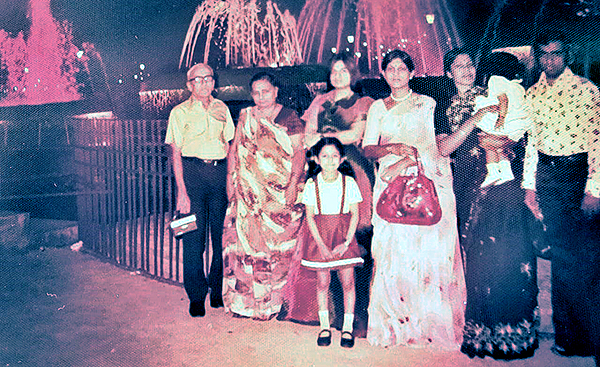

The Ashar family in Kuwait.

A family torn apart

“Those days passed in a blur and a sea of tears,” says a sombre Shanta. “We didn’t know how bad things were going to be, but that fear of never seeing each other again clawed at all of us.” With war looming on the horizon and no immediate avenue available for Ramesh to depart from Kuwait, Shanta and Kiron took the first flight to Mumbai and decided to wait out the separation in India. But as hours turned into days, which turned into weeks, the worry and fear continued to grow.

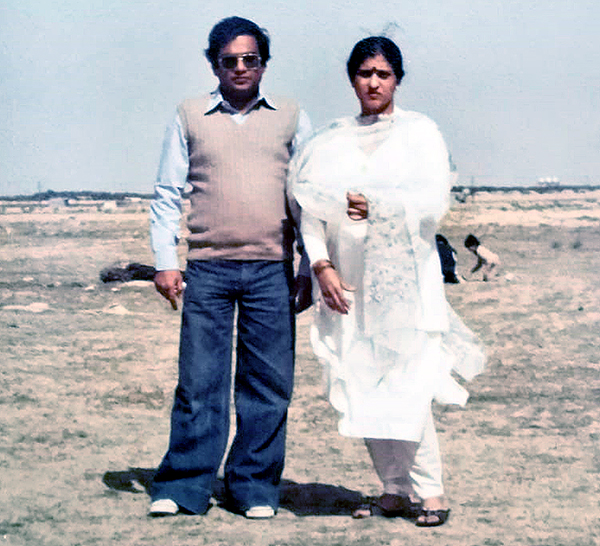

Shanta and Ramesh Ashar in Kuwait. Shanta was in Dubai at the time of invasion, while her husband was in Kuwait City.

For Ramesh, the reality on the ground was far worse

“We had no way of knowing what was happening around us. What little information that trickled down was largely hearsay and one that travelled the circuit between family and friends,” recalls Ramesh.

“The TV stations were shut down within hours of the invasion and all outside communication ground to a halt 24 hours later.”

The Iraqis had shut down international phone lines, with families and loved ones cut off from the world even as the UN condemned and imposed strict sanctions on the country.

“Our only window to the outside world was BBC Radio and we would sit around it for hours daily trying to ascertain basic information of how things were progressing beyond our four walls,” says Ramesh.

The Ashers, who are six-generation expats in the Gulf, have collectively spent close to 100 years across Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait and the UAE. Shanta spent much of her early years in Bahrain, with marriage bringing her to Kuwait, where she joined Ramesh and his family — including his sister, brother, sister-in-law and a volley of nieces and nephews. Here she spent another two decades raising her own two daughters.

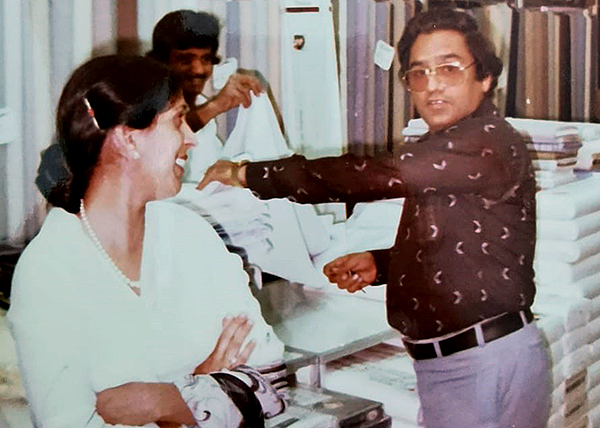

Ramesh Ashar spent his formative years in Kuwait before having to flee during Iraq's invasion.

“What I had loved about Kuwait was its progressive outlook on life,” recalls Shanta. “Despite being a Gulf nation and people expecting a conservative way of living, Kuwait was exceptionally ahead of its times.” Daughter Kiron, who grew up in the city, tends to agree.

“Long before raffles and vehicle draws played a large part in marketing mechanisations in other Gulf states, Kuwait had pioneered it with mum even winning a car during our time there.” That car, and much of their belongings, are now part of a forgotten memory of another time in their lives, locked away in the dark recesses of their mind.

Kiron has never returned to Kuwait in these 30 years, with the trauma of the Gulf War still haunting her decades later. “We grew up in the shadow of a conflict with the Iraq-Iran war in the 80s, a looming reality that played its part in the background even when we were kids,” says Kiron. “Emergency drills, the distant sounds of explosions were something we were all privy to from a young age. But the reality of a conflict knocking on our very doors was something none of us had fathomed.”

While Kiron and Shanta watched the war unfold on CNN in those early days of the invasion, life for Ramesh played out very differently. “Those first few days felt like a curfew had been declared. Nobody stepped out of their homes out of sheer terror, not knowing if shoot on sight orders had been implemented,” recalls Ramesh. “It was after the third day that supermarkets and groceries had been granted permission to open, allowing many of us to stock up on basic essentials.”

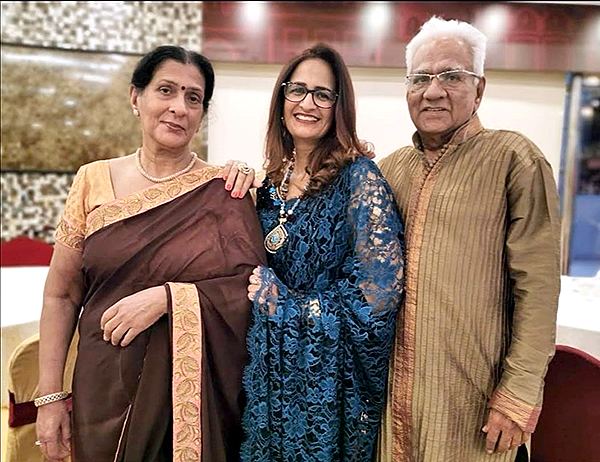

Kiron Khira (far right), who grew up in Kuwait, called the country very progressive during her formative years.

As Ramesh’s relatives lived on the outskirts of the city, he would drive down there daily, having meals with his brother’s family, while returning home to protect his belongings as stories of widespread looting began to gather steam. Money was scarce in those early days, with the Iraqis declaring the Kuwait dinar a defunct currency.

As the need for cash increased, banks were finally reopened with a new coinage in circulation.

Escape from Kuwait

By August 9, Operation Desert Shield had come into effect, with US forces gathering steam in the Gulf even as Saddam Hussein built up his troop strength to approximately 300,000 in Kuwait.

For Indian nationals in the country, the timing was detrimental to plot an escape even as the fear of chemical warfare hung over their heads. Ramesh says he and a few of his friends started plotting their escape.

Aid from the Indian Embassy was not forthcoming at that time, but news soon travelled that the ousted Ambassador to India in Kuwait was running rescue operations from Basra, Iraq. As the days turned into weeks, several of them mustered their courage, opting to drive into enemy territory in a bid to escape the war zone.

Ramesh and Shanta Ashar during their time in Kuwait in the late 80s.

Difficult decisions

“We were eight of us who piled into two cars and decided to undertake the drive to Basra,” reveals Ramesh. “Because the city lies close to the Kuwait border, we were fairly confident we could make this drive without incident.” However, the journey meant saying goodbye to his family who chose to stay behind.

“It was a difficult decision with my brother’s family, along with my sister, choosing to stay in Kuwait. They had young kids with them and didn’t want to risk their lives. It was very difficult to say goodbye but we held on to hope that we would see each other again in the future one day,” says Ramesh.

Packing up meagre belongings and some American dollars to sustain them for any emergency, two cars set forth for Basra with hope and fear taking up equal place in their hearts. The drive, Ramesh recalls, was largely uneventful, with the Iraqi checkpoints waving them through after learning they were Indian nationals.

“Upon reaching the hotel where the Indian Ambassador was stationed, we realised there were hundreds like us who were in similar situations, eager to escape before a full-fledged war broke out,” he says.

Escape was a possibility but their only avenue was to either drive all the way to Amman, Jordan where refugee camps had been set up for people escaping Kuwait or to reach Baghdad where the Indian government had facilitated buses and flights to ferry stranded Indians to Amman. Yet, Baghdad lay deep inside enemy territory, which was another eight hours drive from Basra.

Air India helped evacuate 170,000 people from Amman.

Behind enemy lines

After a discussion with fellow travellers, Ramesh and a few of his friends chose to head for Baghdad next and use their dollars to book a flight to Amman. Kiron recalls hearing of their plan and having a near panic attack.

“We had no contact with my father all through his time in Kuwait and then suddenly, we hear from him with news that he’s in Iraq and plans to drive to Baghdad. We were terrified.” The drive was a harrowing one for the brave men, as they drove deeper behind enemy lines with a vehicle brandishing Kuwaiti license plates.

“Someone was surely watching over us that we arrived in Baghdad without too much fuss and the dollars helped us secure the first flight out to Amman,” he says. “I don’t think we could ever repay the debt owed to the Indian government, which did everything possible to help us return home.” The 1990 airlift of Indians from Kuwait was carried out between August 13, 1990 and October 20, 1990 following the invasion.

Air India helped evacuate 170,000 people from Amman, with the monumental undertaking even finding a mention in the Guinness Book of World Records for the most people evacuated by a civil airliner. “India’s Foreign Minister I.K. Gujral was instrumental in making this happen,” says Kiron, who remains grateful even today. “He even undertook the first flight to Amman himself to ferry women and children to India.”

Shanta, Kiron and Ramesh Ashar have now settled in Dubai. While the husband and wife have returned to Kuwait since the invasion, Kiron confesses she has been unable to overcome the trauma of the Gulf War.