LACK OF TESTING, SOARING DEATHS

In the world’s populous nations, millions of daily wage earners were thrown out of work. Strict screening at border points were imposed, contact tracing was done, health workers were trained and testing capacities scaled up, which helped curb the rate of transmission. But not for long.

Reuters

A homeless woman and child wait to receive food during a 21-day nationwide lockdown to slow the spread of the coronavirus in Kolkata, India, on April 3, 2020.

If US President Donald Trump touted the increased testing facilities in his country, in India and Pakistan this was not the case, at least in the early days of the coronavirus.

By March 24 there were fewer than 600 cases in India, with many saying it was an undercount. But that did not stop Prime Minister Narendra Modi from announcing the world’s largest lockdown, asking 1.3 billion Indians to stay home for 21 days to fight the spread of COVID-19. The predictions of carrying on without a lockdown were dire. Without control measures the virus could affect 300 million to 500 million people by the end of July, scientists had said.

Reuters

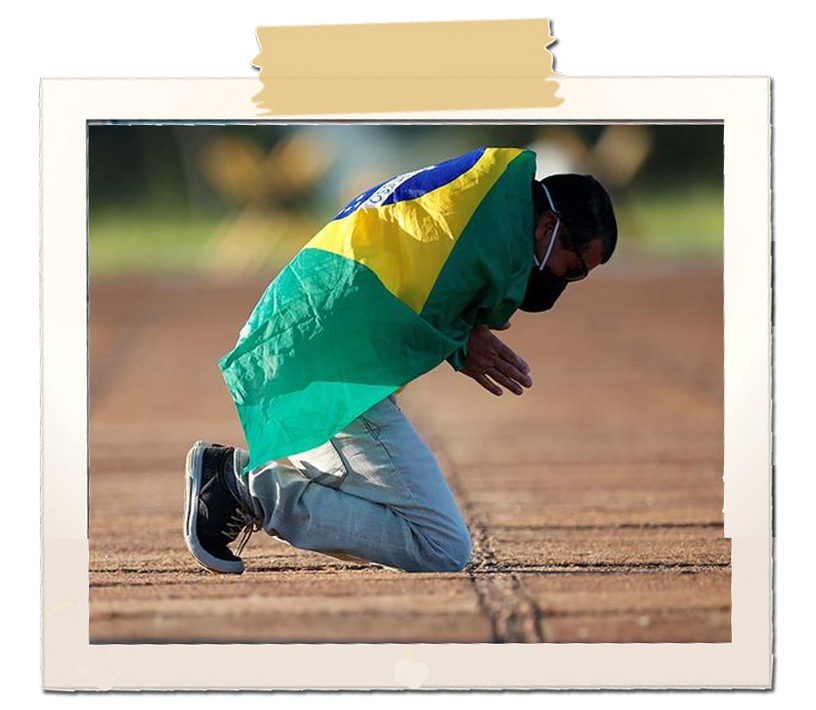

A man prays in front of the Alvorada Palace, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, in Brasilia, Brazil, April 28, 2020.

The impact of lockdown

Millions of people who depended on daily wages were thrown out of work. Migrant workers around the country made a beeline to get on to buses and trains, or simply walked and cycled hundreds of kilometres home.

With little access to food or healthcare along the way, many died. An economic package to support the poor was announced, providing grain and free cooking cylinders.

The fight against the coronavirus was also spruced up – people were screened at ports of entries, contact tracing was done, health workers were trained, and testing capacities scaled up. The early lockdown helped plan and implement a strategy. The decision to produce protective gear locally showed the country was gearing up for the long haul.

There were success stories in some states in the early days of COVID-19, with Kerala being singled out for the meticulous nature in which it kept the cases down. Using its experience in tackling the Nipah virus in 2018, Kerala ‘hoped for the best but planned for the worst’, in the words of state health minister, K.K. Shailaja.

Despite large numbers of cases in Maharashtra, Dharavi, one of Asia’s biggest slums, used ‘test, trace, isolate and treat’ to good effect, ensuring that virus transmission had dropped to sporadic cases.

In Pakistan, the case was no different. After a slow start, the virus made up for lost time and began to take a heavy toll on the population.

Hospitals were overflowing with patients, medical staff and planners braced for large scale deaths. Businesses were shut, flights were grounded, traffic came to a halt, the rich and the poor fell victim to the coronavirus.

And then the cases came down without any apparent reason, confounding scientists. Many thought herd immunity had kicked in. But then, as with most cases related to the coronavirus, this phase too was short-lived.

Elsewhere in the world, in Brazil, a large majority of the people refused to comply with social distancing methods, thanks in part to President Jair Bolsonaro who felt that the people were unnecessarily worried about the virus.

The health minister was fired when he opposed the president’s stance on social distancing and his replacement resigned soon. It did not take long for Brazil to emerge as the new epicentre of COVID-19, with the world’s highest rate of transmission and a health system teetering on the brink of collapse.