Italy: Death and distress

Scientists had warned that coronavirus was highly infectious. In many ways, health officials and policy makers were working with limited information and hoping that COVID-19 would spare them by some stroke of luck. Then the disease spread like rolling disaster.

Wuhan was far away. Was there need to worry about COVID-19 infecting people on the other side of the earth?

Yes, the Chinese city was shut down. Yes, the scientists had warned that coronavirus was highly infectious. And yes, people were still flying in and out of countries. After all, we have seen off other infectious diseases like SARS, MERS and H1N1.

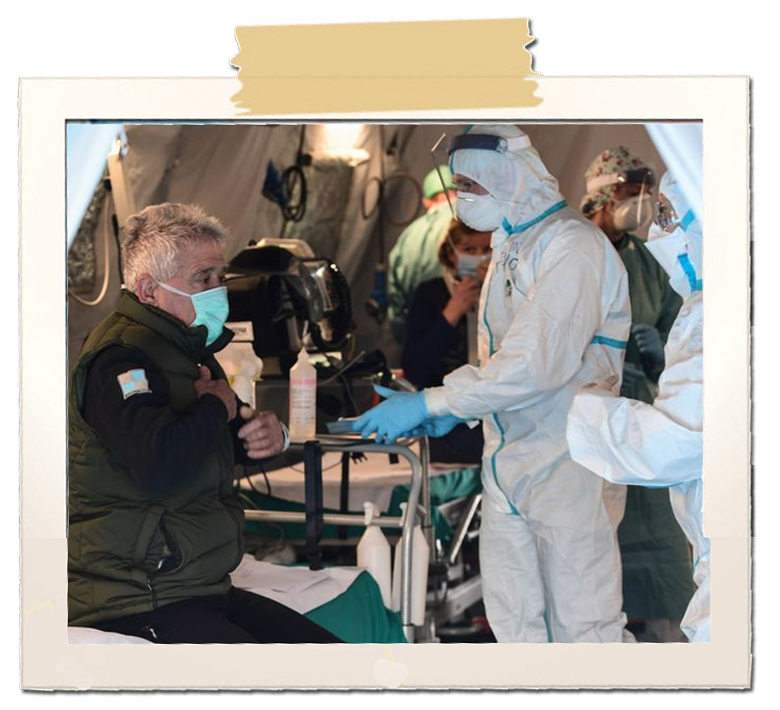

AFP

A patient waits to be tested for new coronavirus at a temporary emergency structure outside a hospital in Brescia, Italy, in March 2020.

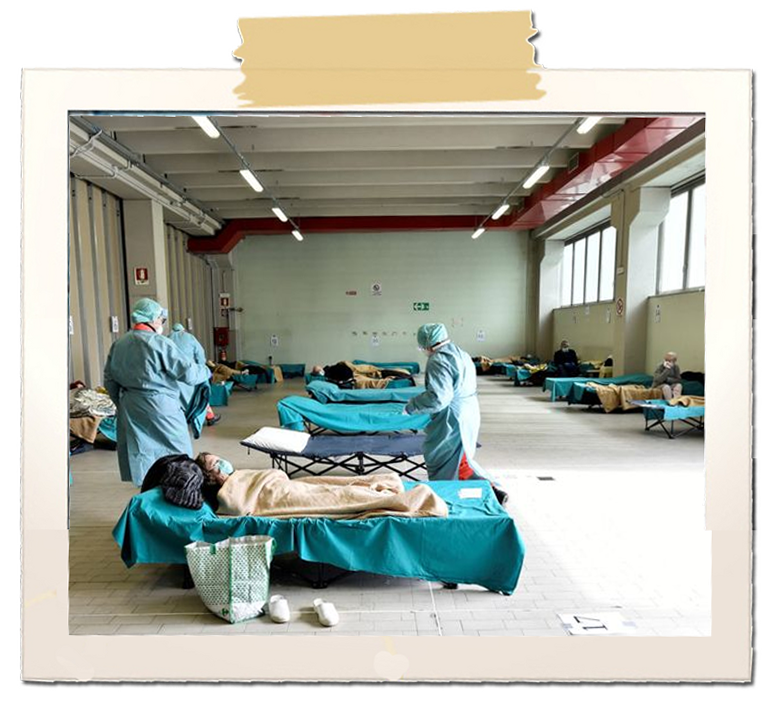

Reuters

Medical personnel help patients at the Spedali Civili hospital in Brescia, in March 2020

So if one day we were told that with summer approaching there was nothing to fear as the virus would die in the heat, on another day this advice was not true at all. In many ways, policy makers were working with limited information and hoping that COVID-19 would spare them by some stroke of luck.

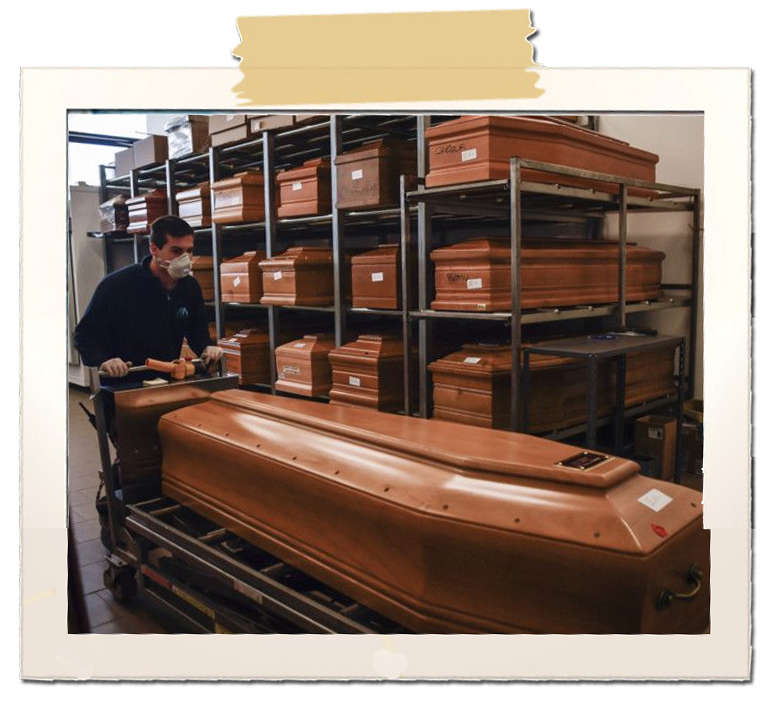

AP

A worker takes away a coffin in the Crematorium Temple of Piacenza, northern Italy, in March 2020. The crematorium was saturated with corpses awaiting cremation due to the coronavirus emergency.

Therefore, when the virus did hit, officials failed to address the unprecedented challenges presented by the crisis.

When Italy detected its first case of COVID-19 on January 29, 2020, in two Chinese tourists, the authorities were sure that they had taken adequate measures to protect the people. The next day, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte declared a state of emergency and blocked flights from China. Very soon, Italy became the epicentre of Europe’s coronavirus crisis.

Some scientists believe that the coronavirus circulated freely in Italy from at least mid-January – with many of those infected showing no symptoms. The initial cases were not spotted and the virus spread fast.

On February 18, a 38-year-old man went to the hospital in Codogno with high temperature, but the medical staff did not diagnose him with coronavirus. By the time he returned to the hospital when the symptoms got worse, he had become the first locally-transmitted case in Italy.

Very soon, towns were put under lockdown. The government issued a decree that prohibited the movement of people in the country and the closure of business activities leading to Italy’s biggest crisis since the Second World War.

AFP

A cemetery employee closes the gates of the Monumental cemetery of Bergamo, Lombardy, as relatives of a deceased person wait outside, in March 2020.

What went wrong in Italy?

On the face of it, the country did all that it could, given the circumstances. But the health services were overwhelmed by the magnitude of the attack. It just could not cope. Also, the messages of “just a little more than normal flu” did not help prepare the country and the people.

Restrictions on bars and restaurants were relaxed just when the cases were rising. Politicians continued to shake hands and sent out the message that the economy should not be allowed to suffer for the sake of a virus. Without complete lockdowns, the people were on the streets. Italy’s high average age, with the elderly having pre-existing conditions, led to a surge in deaths.