The road to war: Intransigent Saddam bites the bullet

Massive multinational firepower forces Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait

The military action has earned different names including Operation Desert Storm. the Kuwait Liberation War; the First Iraq War; and the Second Gulf War – distinguishing it from the 1980-1988 war between Iraq and Iran.

Cairo: Despite Saddam Hussein’s threats against Kuwait in the weeks leading up to the invasion, the latter did not mobilise. Kuwait, it seemed, had hoped that Arab efforts would defuse tensions with neighbouring Iraq and blunt Saddam’s threats. When Saddam poured about 100,000 of his forces across the border into the small emirate on August 2, 1990, most Kuwaitis were on summer holiday. The Iraqi forces overran and occupied Kuwait in two days. But this does not mean they had a military picnic. On the contrary, they faced stiff resistance.

Fierce fighting

The Kuwaiti Emiri guards fiercely fought the Iraqi forces outside the Dasman Palace as the invaders apparently sought to capture emir Jaber Al Ahmed Al Sabah who was able to leave for neighbouring Saudi Arabia. An hours-long battle raged outside the palace, where Prince Fahad Al Ahmed, a member of the ruling family, was killed. He was later dubbed the “Martyr of Dasman”.

Puppet regime

Having seized Kuwait, Iraq set up a puppet government there led by Alaa Hussain Ali, an ex-Kuwaiti army officer. Saddam also appointed his cousin Hassan Al Majid as the military governor of Kuwait that Iraq annexed and proclaimed as its 19th province. In Saudi Arabia, Kuwaiti emir Jaber formed a government in exile in the city of Taif. In an August 5 address from exile, the emir sought to boost his compatriots’ spirits against the massive havoc and brutalities wrought by Saddam’s military inside occupied Kuwait. “While aggression was able to occupy our land, it will never be able to seize our willpower and determination. Our willpower and determination are those of our forefathers, who confronted the toughest challenges without let-up or bowing to aggression,” the 64-year-old emir said.

Jubilant Kuwaitis celebrate with their American allies.

Anti-Saddam coalition

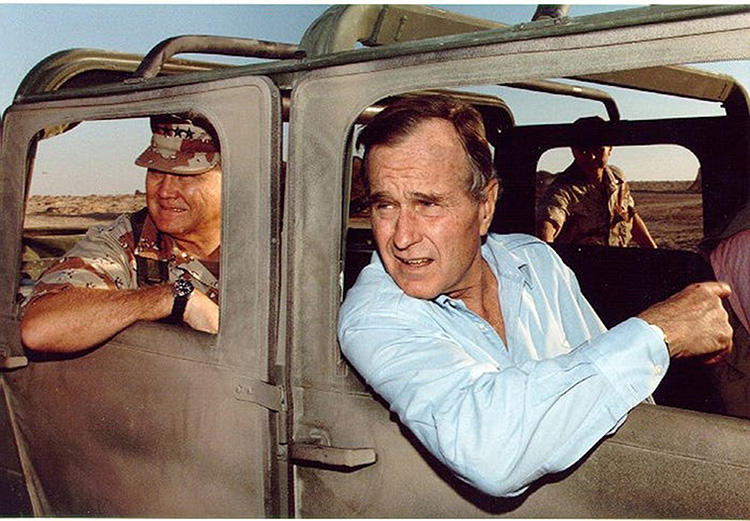

Fears, meanwhile, mounted in the Gulf region that Saddam would not be satisfied with Kuwait and might be tempted to push into other oil-rich countries as his country was saddled with phenomenal debts resulting from his 1980-1988 war against Iran. The US embarked on building a national military coalition to defend allies against Saddam’s dreaded ambitions and drive his forces from Kuwait. In the wake of the Iraqi incursion, US president George H.W. Bush vowed that the invasion would “not stand”, saying all options were open. “They are staunch friends and allies, and we will be working with them all for collective action. This will not stand. This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait,” Bush said on August 5. “What’s emerging is nobody seems to be showing up as willing to accept anything less than total withdrawal from Kuwait of the Iraqi forces, and no puppet regime,” Bushed added, referring to the so-called government installed in Kuwait.

The US-led forces swept into Kuwait and Iraq amid fears that Saddam could unleash chemical weapons to deter the advancing troops.

“We’ve been down that road, and there will be no puppet regime that will be accepted by any countries that I’m familiar with. And there seems to be a united front out there that says Iraq, having committed brutal, naked aggression, ought to get out, and that this concept of their installing some puppet - leaving behind - will not be acceptable,” he told reporters in Washington. On August 6, the UN Security Council imposed economic sanctions, including a full-trade embargo, on Iraq in an attempt to compel its withdrawal from Kuwait. The following day, Bush ordered the launch of Operation Desert Shield, a military effort that laid the groundwork for a multinational alliance, which eventfully pushed Saddam’s troops out of Kuwait.

A day after Iraq missed the UN deadline for withdrawal, a US-led coalition initiated an intense air campaign targeting Iraqi troops in Kuwait and Iraq.

Dramatic buildup

Soon US troops started to arrive in the region and in a matter of weeks, the buildup was dramatic. Other countries followed suit and committed forces to the anti-Iraq coalition. By mid-October, around 200,000 American; 15,000 British; and 11,000 French troops were deployed in the Gulf. On November 29, the UN Security Council issued a deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait before January 15, 1991 or face military action. A flurry of diplomatic efforts got under way for coaxing Saddam into quitting Kuwait and averting military action. Saddam showed no sign of relenting, though. On January 9, US secretary of state James Baker and Iraqi foreign minister Tariq Aziz met in Geneva for talks aimed at ending the standoff. Aziz refused to receive from Baker a letter addressed by Bush to Saddam. The Iraqi official later attributed his refusal to the US president’s language being “not sufficiently polite”.

Bush wrote to Saddam: ‘What is at issue here is not the future of Kuwait - it will be free, its government restored - but rather the future of Iraq.’

Bush’s letter to Saddam

In his letter, Bush demanded Saddam’s full and unconditional withdrawal from Kuwait, warning him of dire consequences if he didn’t. “I am writing to you now, directly, because what is at stake demands that no opportunity be lost to avoid what would be a certain calamity for the people of Iraq,” Bush said in the letter. “I am writing, as well, because it is said by some that you do not understand just how isolated Iraq is and what Iraq faces as a result. I am not in a position to judge whether this impression is correct; what I can do though, is try in this letter to reinforce what Secretary of State James A. Baker told your foreign minister and eliminate any uncertainty or ambiguity that might exist in your mind about where we stand and what we are prepared to do,” he warned. “Unless you withdraw from Kuwait completely and without condition, you will lose more than Kuwait. What is at issue here is not the future of Kuwait - it will be free, its government restored - but rather the future of Iraq. This choice is yours to make.” The ultimatum was issued as more than 900,000 troops of over 30 countries were stationed in the region, mainly on the Saudi-Iraqi border.

After six hours of talks, Baker announced failure to reach a peaceful solution, accusing Iraq of showing “no flexibility whatsoever” to leave Kuwait by the UN January 15 deadline. For his part, Aziz accused the US of double-standards in the Middle East by favouring Israel while failing to deal with Iraq in a “dignified and just manner”. With the collapse of the Baker-Aziz talks, the US Congress authorised Bush to use force against Iraq. As the war loomed larger, inter-Arab divisions deepened. Secretary-general of the Arab League, Chedly Klibi, a Tunisian politician, resigned in protest against the US-led military buildup in the Gulf. Jordan and Yemen expressed support for Saddam and saw the impending war as an “aggression” on the Arab world. Algeria, Tunisia, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, Mauritania, Sudan and Libya voiced reservations over the anti-Iraq coalition. The Gulf countries, Egypt, Syria and Morocco, meanwhile, contributed to the military buildup against Saddam. For one, Egypt, the Arab world’s most populous nation, joined the coalition with around 35,000 soldiers. In the run-up to war, the coalition’s air power was estimated at more than 3,000 warplanes, marking the largest airlift in history. In contrast, Iraq had 750 fighter jets and bombers.

In the run-up to war, the coalition’s air power was estimated at more than 3,000 warplanes.

War begins

A day after Iraq missed the UN deadline for withdrawal, a US-led coalition initiated an intense air campaign targeting Iraqi troops in Kuwait and Iraq. The US codenamed the attack, Operation Desert Storm, commanded by Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf. On January 17, Saddam announced the start of what he called the “mother of all battles”. At the time, the Iraqi army was classified as the world’s fifth largest with more than one million troops. During the 43-day campaign, the coalition mounted nearly 110,000 air raids, including 1,000 sorties in the first 24 hours, crippling Saddam’s forces and causing massive destruction in Iraq. Advanced military technology, including the so-called “smart bombs” were employed by the US-led alliance that primarily sought to destroy the Iraqi air defence system. The coalition launched its strikes from Saudi Arabia and US aircraft carriers in the Gulf. Only one coalition plane was downed by Iraqi forces, who suffered heavy causalities and damage during the relentless bombing. In retaliation, Iraq launched Scud missiles into the Saudi territory, including the capital Riyadh. Saddam also fired missiles against Israel in an apparent attempt to draw Israel into the war and trigger divisions in the Arab countries that were joining the coalition against him. However, Israel did not respond.

Ground assault

The coalition air campaign intensified against Saddam’s military facilities and communication centres in Kuwait and Iraq. The bombing was so massive and effective that it cleared the way for a ground offensive that began on February 23, 1991.

The US-led forces swept into Kuwait and Iraq amid fears that Saddam could unleash chemical weapons to deter the advancing troops. Overwhelmed and outnumbered, large numbers of the Iraqi troops surrendered.

Fiery, chaotic retreat

On February 26, Saddam’s military started withdrawing from Kuwait. The retreating forces set Kuwaiti oil fields on fire, destroying around 85 per cent of Kuwait’s oil wells. Allied forces seized control of a highway linking Kuwait to Basra in southern Iraq, cutting off a major supply route for Saddam’s military.

Thousands of fleeing Iraqi troops in armoured vehicles and tanks used the road to escape, but were bombed by alliance jets, according to Western reports. The road came to be known as the “highway of death”.

On February 28, Gen. Schwarzkopf called a ceasefire, avoiding the temptation of pushing deep into Iraq. “Had we taken all of Iraq, we would have been like a dinosaur in the tar pit — we would still be there, and we, not the United Nations, would be bearing the costs of that occupation,” Schwarzkopf later wrote in his memoir.

Kuwait liberated

On February 27, Bush announced ending the allied combat operations in the Gulf. “Kuwait is liberated. Iraq’s army is defeated. Our military objectives are met. Kuwait is once more in the hands of Kuwaitis in control of their own destiny,” he said.

At least 100,000 Iraqi troops were killed and tens of thousands captured, according to post-war estimates. In contrast, 148 allied personnel were killed in fighting.

The Iraqi government estimated that 2,300 civilians were killed in the coalition air campaign.

The military action has earned different names including Operation Desert Storm. the Kuwait Liberation War; the First Iraq War; and the Second Gulf War – distinguishing it from the 1980-1988 war between Iraq and Iran.

Kuwait’s Emir Sheikh Jaber flew back home on March 14, 1991 after more than seven months in exile. As his plane landed at the Kuwait airport amid a rapturous welcome, smoke from oil fields, torched by the Iraqi military, billowed in sight.