Who runs the world: Scientists

Science and scientists finally found their rightful place in society. It required a pandemic. Besides collaborating on therapy and vaccine, they are now consulted before taking decisions like lockdown, and formulating policies

AFP

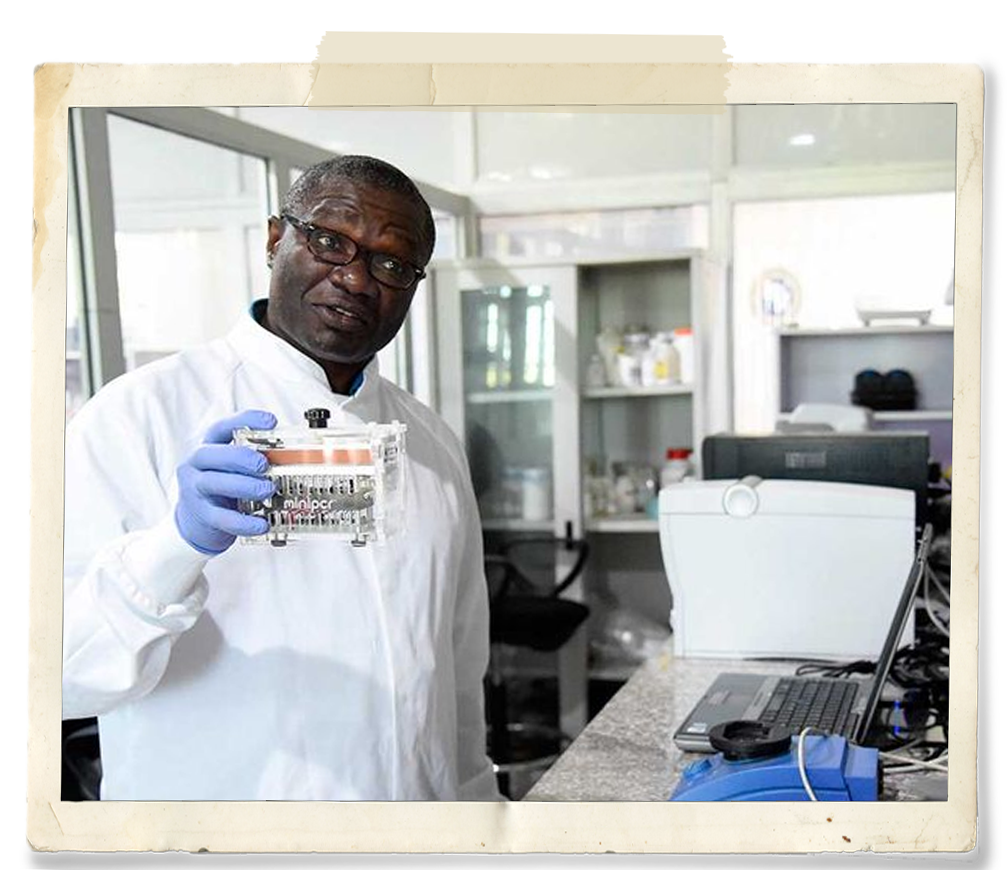

Professor Christian Happi, the director of African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID), holds a miniPCR Thermal Cycler, a laboratory apparatus used to amplify segments of DNA during an inspection of facilities at the centre located at the Redeemer’s University in Ede, southwestern Nigeria, on June 2, 2020.

COVID-19 has brought science and scientists to the fore like never before. The race to find vaccines has broken geographical, linguistic and even field barriers for scientists and researchers.

The last time such collaboration happened was three decades ago, at the height of the AIDS pandemic. However, that is no comparison to the present pandemic because of the ease, speed and efficiency of data collection and sharing across the globe.

While the world fights together, scientists are at the forefront of the battle alongside medical professionals – compressing what is usually years of research to months.

In one example, 11 teams of Indian and US scientists jointly started scouting for an “out-of-the-box” COVID-19 solutions ranging from novel early diagnostic tests, antiviral therapy, drug repurposing, ventilator research, disinfection machines, and sensor-based symptom tracking for COVID 19.

Scripps Research / Andrew Ward lab

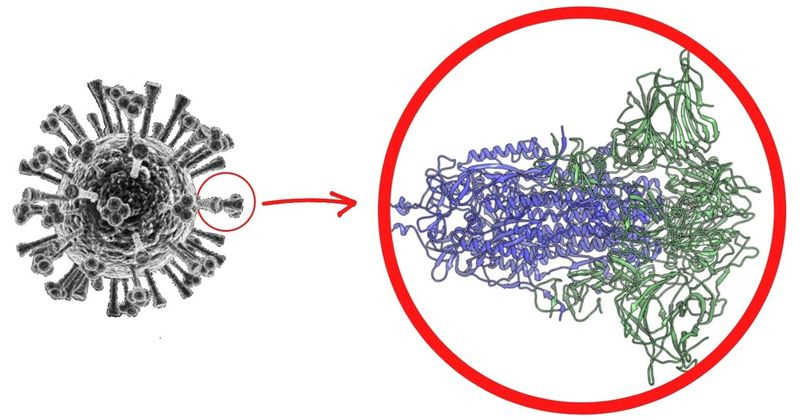

A cryogenic electron microscope image of a SARS-CoV-2. This unique two-piece system has shown itself to be relatively unstable.

Scientific collaboration

Perhaps one of the most useful tools virologists and scientists use in confronting this mammoth task today is the “cloud”.

Read: How the virus mutates

One example of scientific hyper-collaboration is the Global Initiative for Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). This cloud-based database has enabled scientists all over the world to collect samples from patients with COVID-19, sequence the virus’ genetic code, and upload them on to the GISAID server.

That’s how they found mutations, based on the approximately 50,000 genomes of the novel coronavirus that researchers worldwide have uploaded to GISAID and shared by virologists.

This has helped the community figure out minute genetic mutations in SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, thus significantly contributing to man’s understanding of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the Physiological Society has an online journal which offers free access to all published papers from studies across the world.

MedRxiv and bioRxiv are two other online reservoirs where papers are published before peer review so that results can be used for reference well before final approvals and reviews.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) is also collecting and compiling academic and scientific research from across the globe.

The multi-lingual literature cited in the WHO database is updated daily five days a week, and it includes results from searches of bibliographic databases, hand searching, and the addition of other expert-referred scientific articles.

The WHO also has an R&D Blueprint to find and implement diagnostics, vaccines and medicines for COVID-19. The blueprint is intended to improve coordination between scientists and global health professionals, accelerate R&D, and understand how best to tackle the pandemic.

AFP

Laboratory Manager Philomena Eromon (left) at the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID)

Multiple results, multiple methods

While collaborations are on, some countries have pushed to the forefront in making tests and healthcare accessible through their scientists.

Professor Christian Happi, the director of African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID), is one such scientist.

The Cameroon-raised, Harvard-trained molecular biologist, has been at the forefront in the fight against killer diseases such as Ebola, Lassa fever – and now COVID-19.

Prof. Happi’s team has developed a fast-track test that has already been certified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is currently being vetted for use in Nigeria and across Africa.

The test – which resembles the kind of simple dip stick used for pregnancies – costs around $3 each, against around $100 for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, a method that requires an expensive, well-equipped lab.

“I’m not interested in the big PCR machines used in Europe or the United States, which no public hospital here can afford,” said Happi. “I want tests that a grandmother in a village can get done in her rural clinic.”

Scientists and political prowess

The interplay between science and society became stronger during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the weight of scientific evidence is considered when formulating health policies (like lockdowns), it’s no secret that support for science and scientists also has political implications.

A group of American Nobel laureates endorsed Democratic nominee [the President-elect now] Joe Biden after he said he’d trust the scientists on how to fight the coronavirus. The 81-member American Nobel laureates in physics, chemistry and medicine signed a letter supporting Biden’s presidential campaign, citing his “willingness to listen to experts” and respect for international collaboration and immigrant scientists.

“At no time in our nation’s history has there been a greater need for our leaders to appreciate the value of science in formulating public policy,” they wrote. The signers include Steven Chu, a Nobel Prize winner in physics who served as secretary of energy under President Barack Obama; and Kip Thorne, a leading expert on general relativity who consulted on the movie Interstellar.

In an interview with ABC News in August, Biden was asked if he would shut down the country again if scientists recommended it to halt the spread of the coronavirus. “I would shut it down,” he said. “I would listen to the scientists.”